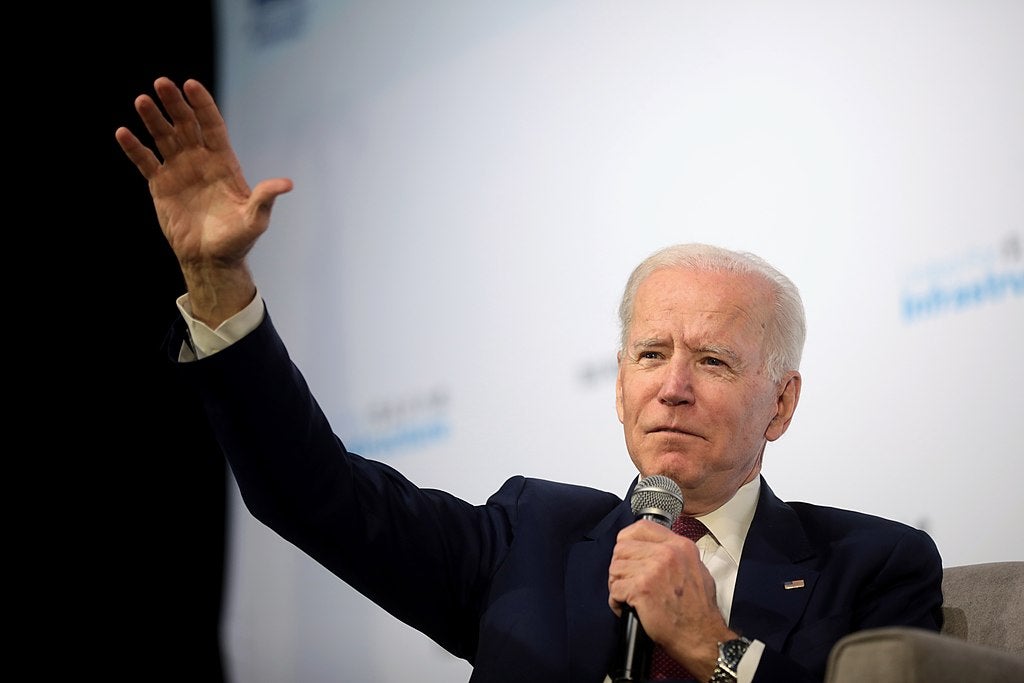

President Biden’s First 100 Days: Our Experts Weigh In

April 27, 2021

Joe Biden took office with an ambitious agenda: tackle the coronavirus pandemic and its economic effects, climate change, immigration reform and racial justice. We asked our experts: how is his administration doing so far?

A Broad Overview

Harry Holzer John LaFarge Jr. S.J. Chari and Professor of Public Policy, McCourt School of Public Policy Joe Biden has had a largely successful first 100 days in office. He has increased COVID vaccinations to over 3 million per day. Congress passed his $1.9T American Relief Plan with very few changes; the legislation is very popular and will provide both relief and economic stimulus. He has also proposed major new legislation – the American Jobs Plan – to build new infrastructure while addressing climate change and providing needed skills training. On foreign policy, Biden is repairing relationships with our allies while confronting aggressive Russian and Chinese behavior. He is restoring respect for the rule of law and for institutions at home. Many challenges remain. The infrastructure bill is unlikely to pass Congress with only 50 Democratic votes, yet Republican support looks nonexistent. Questions remain about how to pay for huge new spending and about possible future inflation or debt burdens. But overall his start has been very promising. John T. Monahan Senior Fellow, McCourt School of Public Policy, Senior Advisor for Global Health to Georgetown University President John J DeGioia, Senior Scholar, O’Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law The ambition and achievements of President Biden’s first hundred days are unprecedented in recent memory. In the past three months, his Administration has led a visibly more effective federal response to COVID, used executive actions skillfully to reverse countless Trump-era foreign and domestic policies, and signed recovery legislation that begins to rebuild our safety net at a scale unseen in more than a generation. I see three factors behind this success. First, Joe Biden has become a kind of “anti-Trump” – presidential, empathetic, and consistent, providing a head-spinning contrast to the tweet -storm recklessness of the last four years. Second, the Administration and its Congressional allies have so far held together their razor-thin majorities to achieve big legislation in this polarized era. Third, Biden and his Congressional allies are making a public case that government can do big things in addressing the public health, race, and climate crises we face; and these political arguments appear to be resonating in ways we have not seen since the Reagan era. Of course, all three factors could shift at a moment’s notice. Biden’s image could stumble, divisions among Congressional Democrats could widen, and public skepticism of government could prove stubborn. But, with the possible exception of border issues, the Administration has achieved a remarkable series of successes in a short period of time. Donald Moynihan McCourt Chair, McCourt School of Public Policy As a public management scholar I am heartened by many of the changes Biden has made. He reversed a Trump policy that would have converted federal civil servants to political appointees, which would have led to extreme politicization of the public service. Much of my research examines administrative burdens in policy implementation. From that perspective, Biden has gotten off to a very good start. In some areas, such as programs for low-income groups or immigration, the Trump administration had deliberately made it more difficult for people to access benefits or rights. Biden reversed that pattern. He removed the ability of states to adopt work requirements in Medicaid for example, and halted a public charge rule that would have made it difficult for low-income immigrants to receive benefits. Biden’s Executive Order on racial equity also prioritized removing barriers that people experience in their encounters with the federal government, and the language on administrative burdens is clearly present in government-wide management directives. After Trump’s promise to deconstruct the administrative state, it’s good to see Biden devote energy to making government work. Mark Carl Rom Professor, McCourt School of Public Policy Big, bold, and fast: That’s how President Biden moved in his first 100 days in office. $1.9 American Rescue Plan? Passed. Cabinet confirmed? Faster than for Trump or Obama. COVID vaccinations? Record pace. Biden leads the US back into the Paris Climate Agreement, and pledges to reduce US greenhouse gas emissions to half their 2005 level by 2020. Biden’s infrastructure proposal, working its way through the Congress, is both massive and popular. But, still. The American Rescue Plan received no Republican votes in either the House or Senate. The most ambitious Republican Senators have voted against virtually every Biden nominee. Senate Minority Leader McConnell has pledged to fight against Biden’s infrastructure proposal “every step of the way”; if it passes, it will be only because McConnell cannot filibuster it. President Biden will continue to reach out to seek Republican support, but that quest will prove futile, at least within the Congress. Given the prospects that the Republicans will regain control of the House or Senate in 2022, Biden knows that his legacy will depend on going big, bold, and fast for the next 100 days, too.

Criminal Justice Reform and Racial Equity

Andrea M. Headley Assistant Professor, McCourt School of Public Policy President Biden made many promises with regard to criminal justice reform and racial equity during his campaign. Since he has taken office, we have seen movement – an executive order advancing racial equity and supporting underserved communities, an executive order reining in the use of private prison facilities, the reintroduction of the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act in Congress, a revival of federal pattern and practice investigations and consent decrees, a declaration of April as “second chance month,” diverse judicial appointments and nominations to high-ranking positions in the Department of Justice, the American Rescue Plan Act that includes funding for substance use and mental health programs, as well as the American Jobs Plan proposal, which earmarks money for community violence intervention programs. These all represent steps in the right direction. However, I hope to see more done to decrease reliance on the criminal justice system, reduce the number of people incarcerated, ensure police oversight and accountability, prioritize crime prevention, and root out systemic racism and discrimination in the justice system.

Government Spending

Keith Hall Professor of the Practice, McCourt School of Public Policy The Biden administration inherited a significant number of challenges and they have responded very quickly in a remarkable number of ways. The pandemic and related recession problems are the most pressing and, in a way, the most straightforward to address. After that, the American Jobs Plan and the administrations’ first annual budget proposal sets administration priorities for life after the pandemic. The clearest signal that I see from this is that they want more government. We are coming off unprecedented levels of government spending related to the pandemic. Total government spending in 2020 was extreme — $9.1 trillion or $27,650/person. Thanks in part to the administrations’ American Rescue Plan, the federal government alone will add another $6 trillion in spending this year. That is a lot of spending and a lot of new debt. But rather than trying to correct the federal balance sheet (as most of us would if our own household budgets took this kind of hit), the administration has offered up trillions of dollars in new spending. Even if this new spending is paid for with higher taxes, there is a significant cost to this. More government means less private sector. To illustrate this point, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) just released an exercise where they estimated the likely economic effect of having a permanently larger federal government. As always for CBO, this was an application of scientific evidence to public policy. They found that a 5 to 10% larger government (with a matching increase in tax revenue) would ultimately result in a 3 to 10% lower level of national income (slightly less if some of the new spending raises productivity). This is the loss of several years worth of potential income growth.

Education and Children

Nora Gordon Associate Professor, McCourt School of Public Policy I’m an education researcher, but the part of President Biden’s first 100 days that I find by far the most exciting has nothing to do with schools. It’s the child tax credit. The loss of in-person schooling for so many during the pandemic emphasized the many roles American public schools are asked to play in the absence of a more robust safety net. Schools couldn’t do it all during COVID, but they can’t do it all without COVID either. Hooray for cash!

Climate Change and the Environment

Sheila Foster Scott K. Ginsburg Professor of Urban Law and Policy, The McCourt School of Public Policy and Georgetown’s Law Center President Biden has hit the ground running on a number of his campaign promises. On environmental and climate issues, he has taken concrete steps to reassert American leadership by making firm commitments to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by half. He has also, importantly, made specific promises on environmental and climate justice. For instance, he signed an executive order with a goal that 40% of overall benefits flow to “disadvantaged communities” from “certain federal investments” in areas such as clean energy and energy efficiency, public transit, and affordable and sustainable housing. Under the Trump Administration, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) referred the fewest number of criminal anti-pollution cases to the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) in 30 years. In contrast, President Biden promises to establish an Environmental and Climate Justice Division within the DOJ. President Biden has also embraced the development of a Climate and Environmental Justice Screening Tool, a tool that builds on EPA’s existing EJSCREEN, to identify communities with the greatest cumulative pollution burden, and the most vulnerability to the effects of pollution, using a host of social vulnerability indicators that go beyond the relatively narrow considerations in the federal pollution control standard-setting process.