The cost of air pollution on your health… and the housing market

New research from McCourt School expert Lutz Sager measures the effects of the Clean Air Act on air pollution, exposure disparities and house prices.

The Clean Air Act, the flagship federal legislation regulating air emissions, was first enacted in 1963. Since the 1970s, every decade has brought new regulation — from reducing auto emissions to phasing out ozone-depleting chemicals.

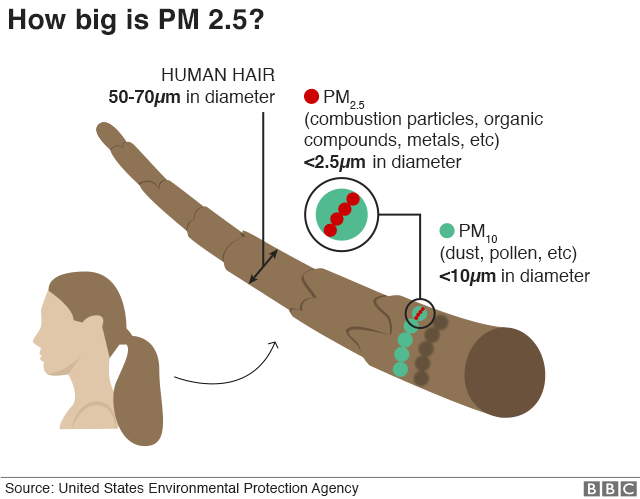

In collaboration with the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment at the London School of Economics, McCourt Assistant Professor Lutz Sager evaluated the effectiveness of the latest Clean Air Act rules for fine particulate matter (PM2.5) pollution. Particulate matter, which is 30 times smaller in diameter than a piece of human hair, is often only visible through a microscope, while other times, it is dark enough to be seen circulating in the air.

“Air pollution from fine particulate matter has substantial negative effects on health, productivity and behavior,” said Sager. “It can lead to higher mortality, greater risk of asthma and heart attacks, and slower performance, especially among workers doing more physical, manual labor.”

Sager’s previous research has also shown that individuals are potentially more aggressive on days when there is a high concentration of PM2.5 pollution in the air. One possible explanation for this is that the particulates potentially trigger cortisol, the body’s primary stress hormone.

The effect of air quality on house prices

The World Health Organization and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) have been measuring air pollution for decades. In 2005, the EPA used air quality monitors to calculate an average level of exposure to PM2.5 pollution in the United States. Historically-problematic areas and many new cities became subject to higher regulation by state and federal agencies.

Sager found substantially improved air quality in regulated areas in the decade that followed, underscoring the Clean Air Act’s contribution to better air quality. Sager also found that more polluted areas experienced faster air quality improvements even when they were not regulated — possibly due to modern advancements in manufacturing, more cars with less emissions and better environmental policies at the national level.

“It was important that we accounted for pre-existing trends in pollution improvements,” said Sager. “Failing to account for these trends risks overstating the pollution reduction benefits of regulation.”

The resulting air quality improvements are also reflected in higher house prices. Sager found that houses in cleaner air environments were bought and sold at higher prices than houses in less-regulated, more polluted geographic regions.

“This trend is visible in places that became more-highly regulated after 2005, like Cincinnati, Indianapolis, Los Angeles, Chicago and New York City, among other major metropolitan areas,” said Sager. “Many such places experienced bigger improvements in air quality and bigger increases in house prices, reflecting that people seem to place a higher value on properties where the air is cleaner.”

Disparities in race and pollution exposure

“The biggest source of fine particulate matter pollution comes from burning fossil fuels,” said Sager. “While pollutant concentrations can vary across geographic regions, high pollution areas tend to be those around power plants, construction sites or major highways, for example.”

Although highly-regulated areas are dispersed across the country, bad air quality disproportionately affects minority and disadvantaged groups, and people living in urban areas. The racial gap and urban-rural divide in exposure to toxic particulate matter may reflect factors beyond geographic distribution, such as wealth disparities and uneven policies.

Sager found that Clean Air Act rules have helped narrow both gaps, largely due to extra attention being paid to high pollution areas, where state and federal agencies have increased regulation and monitoring.