How can educational institutions safely expand their use of student data?

Massive Data Institute researchers conducted more than 40 stakeholder interviews with state education agencies, U.S. Department of Education officials, postsecondary institutional staff and edtech providers to investigate their interest in advanced data privacy technologies.

Data are generated in the education sector at rapid rates. Institutions, states and districts, and educational technology (“edtech”) firms collect data on students’ learning patterns and outcomes. However, the current demands of these education data owners often exceed their technical and institutional capacity. Consider this hypothetical example:

Lisa is a statewide longitudinal data system (SLDS) manager. Her data on her state’s public school K-12 students have mainly stayed put on its secure server, accessed internally through their vendor’s interface. But certain external needs have been rising to the surface in recent years:

- Districts want to know the effectiveness of their new high school career and technical education (CTE) programs.

- School officials want the SLDS data linked to law enforcement data so they can better direct student support services.

- Lisa’s colleagues want to reduce the number of individuals viewing and sending sensitive data for their compliance reporting purposes.

Lisa wants to use her SLDS data to better serve her students and districts but is not sure how to proceed. She is reluctant to share her SLDS data with outside parties due to her concern over exceeding her agency’s authority or violating laws such as the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA). What should she do?

This spring, the Massive Data Institute (MDI) at Georgetown University’s McCourt School of Public Policy conducted a landscape analysis of data privacy in the K-12 and postsecondary education fields, to help answer questions such as Lisa’s. MDI interviewed over 40 education data owners about their current data infrastructure and interest in privacy preserving technologies (PPTs). In our resulting report , we identify existing examples in which education data owners used PPTs to enable greater utility of and inquiry into their student data. We also highlight the barriers preventing PPTs from being widely adopted, and we make recommendations for government, foundations, and associations to help overcome these so that K-12 and postsecondary institutions can ultimately use these insights to improve student outcomes.

PPTs as potential solutions to education data privacy concerns

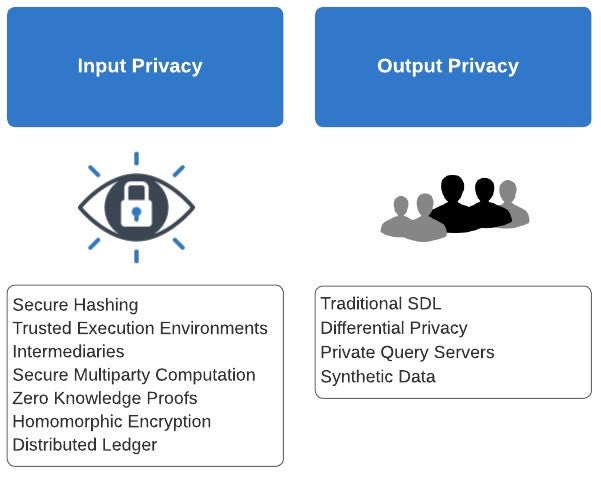

Privacy preserving technologies (PPTs) are a group of cryptographic techniques that increase data protection while allowing for greater data utility. They work by masking personal identifiers, automating access rules, and altering outputs to protect individuals and groups from harms. Here, we show the various ways education data owners can mitigate privacy risk across input and output privacy. Input privacy refers to the protection of student records from unauthorized access during matching or analysis, whereas output privacy refers to the protection of student identities when publishing statistics or results.

All solutions listed here are PPTs, with the exception of intermediaries and statistical disclosure limitation (SDL). While we recognize that many successful approaches involve blending more and less technical methods to meet organizations’ privacy objectives, PPTs allow for greater and safer data linkages, data sharing, and data mining than traditional methods alone. PPT adoption can improve student service delivery, education outcomes measurement and program evaluation, internal agency operations, and institutional compliance reporting.

In fact, they already have. PPTs have been implemented by Washington state’s education agency to allow external researchers access to school and workforce data, at the Georgia Policy Labs to securely link government agency and school district data, and by the U.S. Census Bureau to safely publish earning and employment outcomes for postsecondary institutions. Through our qualitative research, we found 18 total PPT demonstrations or implementations such as these in the current education space, with three more in development.

What our interviews revealed

Over the course of three months, we interviewed over 40 stakeholders across state education agencies, the U.S. Department of Education, postsecondary institutions, and edtech providers.

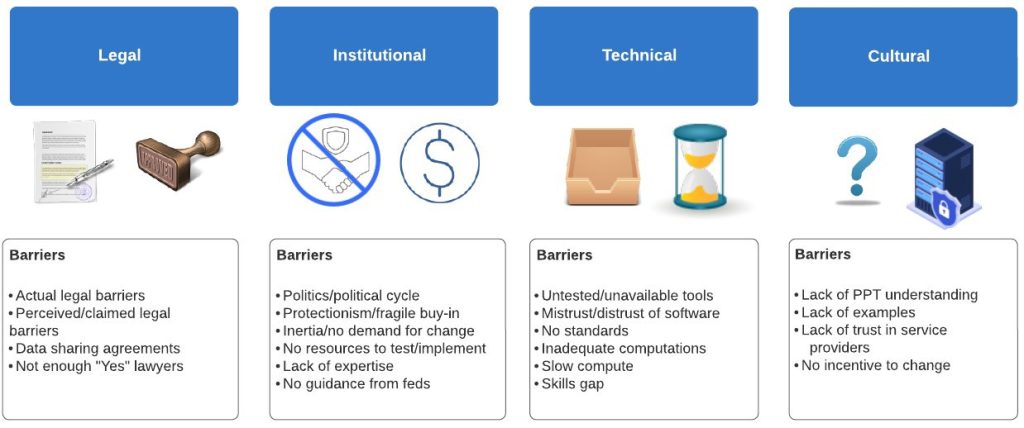

The interviews exposed a wide range of PPT awareness and adoption: Some interviewees, such as those listed above, are currently integrating advanced PPTs into their data systems, while others did not know what PPTs were. Most commonly, though, the stakeholders possessed some knowledge of PPTs but were not considering these technologies as serious options for their organizations. When digging into the origins of their reluctance, we heard in our interviews that PPT consideration often stalled due to four main barriers: legal, institutional, technical, and cultural.

Recommendations for moving the needle

To address these barriers, we see a need for cross-cutting and coordinated efforts across specific investment areas. Specifically, we put forth the following recommendations to advance PPTs in education:

- Explain PPTs: Produce accessible briefs, for the public and data owners, explaining what PPTs are, how they work, and how they interact with other privacy laws.

- Train at Many Levels: Train agency and institutional staff on open-source PPT solutions, as well as “yes” lawyers who can advocate for these advancements within their legal and regulatory realms.

- Engage Champions and Skeptics: Conduct town halls, roundtables, and task forces for both the public and administrative gatekeepers to affirm the value proposition of PPTs and unpack the privacy sticking points.

- Invest in Science: Allow for the continued refinement in PPT methodology for the newer technologies, and investigate the limitations, such as the tension between disaggregate statistics for equity research and privacy protection of those data subjects.

- Develop Guidance and Regulation: Publish guidance on how FERPA and other relevant privacy laws allow you to share data via PPTs, and outline a process for “safelisting” software and data products.

- Fund to Fill Gaps: Fund more examples of PPTs that address valuable education use cases, as well as trainings for agencies, targeted outreach to states, and data integrator roles.

While the federal government, such as the U.S. Department of Education, the National Science Foundation, and the Office of Science and Technology Policy, can certainly play a role in adopting these recommendations, we also envision a consortium of groups and associations participating, such as a national association of school technology and privacy officers.

These investments will support a virtuous cycle of PPT development and use, connecting efforts across government agencies, institutions, academics, and industry. Progress is likely dependent on philanthropic support. In our next phase of this research, we plan to develop an outreach and awareness campaign that will set the stage for future funding, demonstrations, and standardized guidance.

The full paper can be found here . For our other MDI privacy publications, please see our website .